Welcome to Bidwell Lore number 171! This week we wrap up our series on Agrippa Hull with an essay from Electa Jones.

There is still time to donate to our Annual Appeal! Your support allows the Museum to produce this newsletter, create engaging history programs, and maintain this beautiful house and property. Click HERE to donate today and select Annual Appeal from the drop-down menu under Designation at the left.

This series would not have been possible without the incredible help of Josh Hall and India Spartz at the Stockbridge Library and Archives. Most of the information we will be sharing was obtained from the Museum and Archives and their help was invaluable in putting together this story. -Rick Wilcox

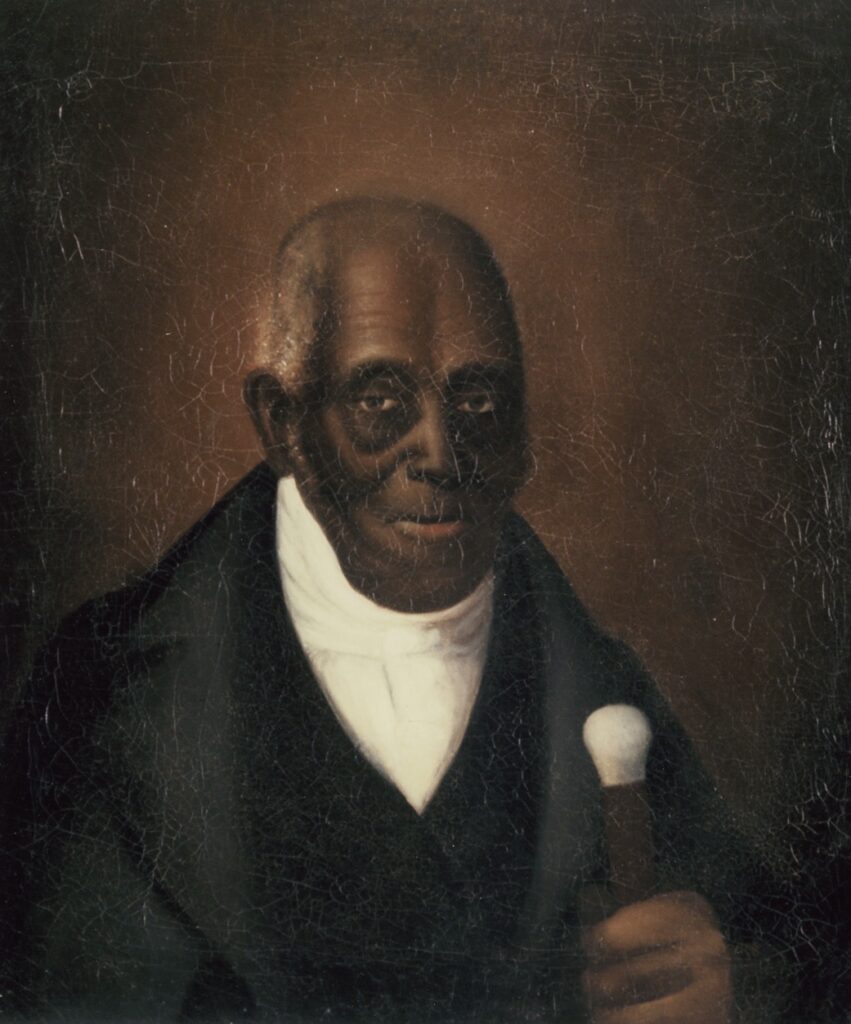

Saying Goodbye to Agrippa Hull

Rick Wilcox, 2022

For the last installment in our Agrippa Hull series, we turn to someone whose name should be familiar to those of you who have been reading the end notes along the way: Electa Fidelia Jones. The author of Stockbridge Past and Present, Or Records of an Old Mission Station, Electa was the daughter of Josiah and Fidelia Jones. Josiah Jones, born September 7, 1767, was the son of Josiah Jones, Jr. And Josiah Jones, Jr. was the son of Josiah and Anna (Brown) Jones [1] who were one of the four families to arrive at Stockbridge as required by the 1737 Indian Town Charter. Electa’s history of Stockbridge was published in 1854, just months after her death at the age of 47. It is clear that she had immense respect for Agrippa, who died in 1848, as her prose of him reads like a eulogy. It seems fitting that Agrippa’s story should end with the words of Electa Jones.

“Another individual of the same race, who has been peculiarly distinguished in Stockbridge, is Agrippa Hull. – He was born in Northampton, in the days of slavery, but of free parents, who lived near Licking Water Bridge. – At the age of six he was brought to Stockbridge by Joab, and lived there until 1777, when he enlisted as a soldier during the war. His mother had married a second husband, and he was living with his parents; and not liking his stepfather, he said ‘the war could not last long enough for him.’ The first two years, which seem to have commenced during the winter of 1777, he was servant to Col. Patterson; but for four years he was in the service of Kosciusko, the Polish General. He was discharged at West Point, having been engaged six years and two months. He was afterwards in the service of Judge Sedgwick, while that gentleman was a member of Congress in New York.” [2]

“Not long after the case of Mum Bett had been decided, Jane Darby, the slave of Mr. Ingersoll of Lenox, it is said, left her master and took refuge in Stockbridge. She and Agrippa soon agreed to tread life’s path in company; but her master still claimed his chattel, and endeavored to seize her. Agrippa applied to Judge Sedgwick for aid, and obtained her discharge. She was a woman of excellent character, and made a profession of her faith in Christ. Some years after her death, Agrippa married Margaret Timbrook, who still lives respected among us. In 1827, he became hopefully pious, and united with the church, evidently enlisting as he had done in the service of his country -for better or for worse, as long as life’s warfare lasted.

The character of Agrippa could scarcely be called eccentric, and yet it was unique. He was witty, and his presence at weddings seemed almost a necessity. There, as he wedged himself and his ‘good cheer’ into every crowded corner, his impromptu rhymes, and courteous jokes were always welcome. He had no cringing servility, and certainly never thought meanly of himself, or had opportunity to do so, yet he was perfectly free from all airs and show of consequence. He seemed to feel himself every whit a man, while, even in his public prayers, he gave thanks for the kind notice of his ‘white neighbors to a poor black n—-r.’ His language was so simple, and his petitions often peculiarly adapted to the everyday needs of his hearers, or those perishing around him, that a smile was sometimes provoked from the thoughtless; but the true worshiper could not fail to realize his dependence upon the Divine Grace for every right action or emotion, as well as for every breath. Never, until the secrets of all hearts are revealed, con the school-boy, whose merry shouts fell upon his ear had he led the social circle in devotion, know how much of his fairness in games, or his safety for the wiles of those older than himself, was in answer to the fervent prayer of this humble servant of God then ascending for that, so often forgotten, blessing. While he lived too, the church always had one at least, who possessed ‘a spirit of grave and supplication and of supplication.’

In speaking of distinction on account of color, though Agrippa was far from intruding himself uncalled, he would argue –‘It is not the cover of the book, but what that contains is the question. Many a good book has dark covers.’ ‘What is the worst, the white black man, or the black white man? To be black outside, or to be black inside.’

Once, when servant to a man who was haughty and overbearing, both Agrippa and his master [3] attended the same church, to listen to a discourse from a distinguished mulatto preacher. On coming out of the house, the gentleman said to Agrippa, ‘Well how did you like n—-r preaching?’ ‘Sir,’ he promptly retorted, ‘he was half black and half white; I liked my half, how did you like yours?’ [4]

Thus, he was ever ready with a patient, and often a witty answer; and he commended efforts for the good of his race still in bondage, by saying, ‘they will do good by helping them to keep down their bad feeling until deliverance comes.’ He felt deeply the wrongs of his nation, but his feelings rose on the wings of prayer, rather than burst from the muzzle of the musket. Had he lived to the present day, he was not the man to have taken up arms against the laws of his country which he had fought so long to redeem; yet in principle he would have much preferred the fugitive statute of Moses, – ‘Thou shalt not deliver unto his master the servant which is escaped from his master unto thee; he shall dwell with thee, even among you in that place which he shall choose, where it liketh him best.’ Deut. 23: 15, 16; and though unpresuming himself, he might suggest for others, even that of ‘Paul the aged,’ – ‘Though I might be much bold in Christ to enjoin thee, yet for love’s sake I rather beseech thee, receive him that is mine own bowels; not now as a servant, but above a servant, a brother beloved, both in flesh and in the Lord. Receive him as myself.’ – Phil. 8 to 17th.” [5]

The inscription reads: AGRIPPA HULL, / DIED May 21, 1848. / JANE D. / HIS WIFE / there son’s [sic] / James 1825. Aseph 1836. / Margaret, HIS 2nd WIFE

We want to thank you for reading along with us as we shared the story of Agrippa Hull. Moving forward, Bidwell Lore will go from a weekly email to one that we send every other week. The next installment will arrive in your inbox on January 23 when we share a short article about John Hunt, who was mentioned in one of the installments of Agrippa’s story related to the Sedgwick family.

1. Card file at the Stockbridge Town Clerk’s Office, 50 Main Street, Stockbridge.

2. Jones, Electa. Stockbridge Past and Present: Or Records of an Old Mission Station (Samuel Bowles & Company: 1854).

3. Poor choice of words by Electa Jones. Agrippa Hull was a free black and had no master. Jones may have meant to imply Agrippa worked for him for pay.

4. Some references suggest it was Theodore Sedgwick, but he was not a member of the Congregational Society and his behavior towards people of color makes it seem unlikely.

5. Jones, Electa. Stockbridge Past and Present: Or Records of an Old Mission Station (Samuel Bowles & Company: 1854), pp 240, 241, 242.