Welcome to week 54 of Bidwell Lore! In this installment, we begin a new series titled The Plan for the City on the Hill, Township No. 1 – Tyringham and Monterey: The Original “Hinterland Settlement.” In this series, we will share with you the history of Township No. 1 and even more background about the original inhabitants of the Berkshires, the Mohicans. Most of these articles were originally penned about 10 years ago by Rob Hoogs, President of the Bidwell House Museum Board of Trustees, and have been recently updated by Rob.

A New Understanding – Native Americans and European Colonists

by Rob Hoogs

In 2010, I researched and wrote a series of articles about the colonial-era settlement of Township No. 1 which later became Tyringham and Monterey. The original series called “The Plan for the City on the Hill” was published in the Bidwell House Museum’s Newsletter. Since then, the Bidwell House Museum and I have learned much. We are offering this updated and expanded series to add new materials and interpretations, to correct errors and omissions, and to express our new understanding.

The most serious omission from the original articles was neglecting the Mohicans and their indigenous predecessors who had lived here and managed this landscape successfully for many thousands of years before colonization by Europeans. The earlier essays have been rewritten and updated to reflect our personal and collective efforts to learn about the regional history and culture of the Native Peoples.

Our profound thanks are offered to the Stockbridge-Munsee Community who have helped us in our efforts to learn and to “tell their story.” Special thanks especially go to Rick Wilcox who has spent decades studying, appreciating, and advocating for Native culture and history.

This knowledge and appreciation have reshaped how the Bidwell House Museum tells the colonization story. We seek to dispel the many myths and prejudices about the Natives that have previously been written into our “history” books. We hope to more properly relate the context of the land history before and during European colonization of these Native lands.

Contrary to the writings of the English and Dutch “settlers” when they arrived, this was not a “pristine untouched woodland” or a “hideous howling wilderness” with no “civilized” communities. It is very important to understand the context of the Dutch and English Colonization and their usurpation, displacement, and dispossession of the lands of these Native Peoples. Only after we more fully understand the long history of the Native Peoples in this, their sacred homeland, can we begin to tell the story of the European colonists.

I’d like to begin this series with a Land Acknowledgement about the Native Peoples of this area, the Stockbridge-Munsee Community of the Mohican Tribe:

“A Long and Winding Road…”

When you arrive at the Bidwell House Museum today, after traveling along a narrow winding dirt road through quiet woods between mossy stone walls and towering trees, it is hard to realize that this was planned to be the center of a “City on the Hill” in the Hinterland. Yet in the middle 1700s, that’s exactly what the English colonists planned.

But for hundreds of generations before, the land they were planning to “settle on” was the sacred ancestral homeland of the Native Peoples, the indigenous peoples who carefully used and managed the lands. And the narrow, winding road was a well-worn Indian path.

Native Americans

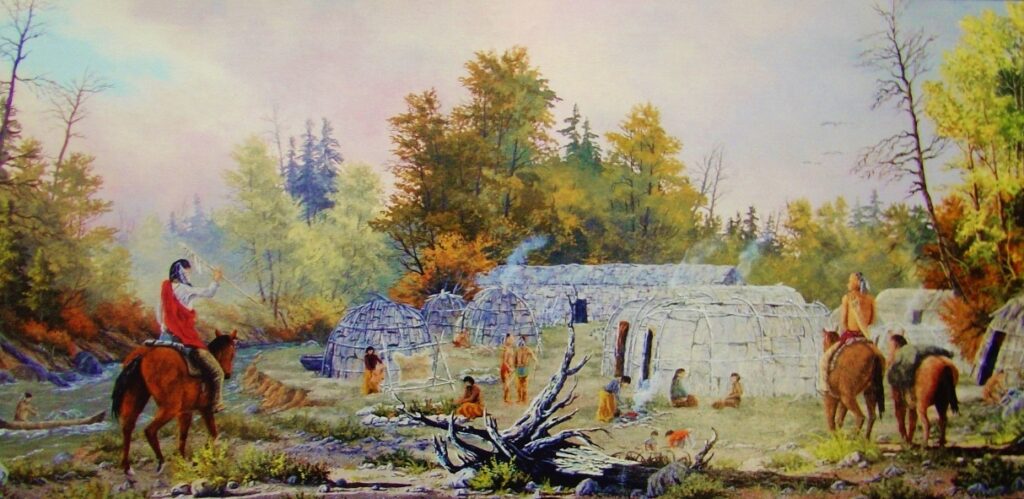

For thousands of years before the Dutch and English arrived, what we now call the Berkshires was home to Native Americans who actively managed and used it. They had a sophisticated interrelated society based on kinships and mutual reciprocal understandings. Their culture revolved around the land: it was both their identity and their livelihood. While it is sometimes said that Natives lived “light on the land,” their land management was actually extensive. Their landscape included numerous trails, seasonal wigwams in their hunting camps, year-round longhouses, and agricultural fields in the warmer river valleys – a vast mosaic of land uses that they periodically improved, used, and then left for fallow to regrow and maintain fertility. Their knowledge of the landscape and the plants that grew here was deep and broad – over five hundred different plants were used medicinally. They built fish weirs along the streams and lakes; harvested mussels from the river bottoms; trapped and traded pelts; made wampum from shells obtained by trading with their coastal cousins and used it to cement agreements and treaties among the tribes. They made canoes from birch bark and by burning out logs. They tapped the abundant ancient maple trees and boiled the sap to make maple sugar that they carried with them on their journeys. They burned off the undergrowth in the woodland once or twice a year to stimulate new herbaceous growth that the deer, moose, bear, and other prey would eat and fatten on; the cleared woodlands also made their hunting easier and more successful in the fall and winter. And they often piled stone on stone to mark their special places. This was always one such special place.

The next article in this series will begin correcting some of the persistent myths about the Native Peoples and our linguistic bad habits that contribute to these myths.