Welcome to week 29 of Bidwell Lore! This week we will explore some correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and Barnabas Bidwell along with Barnabas’ letters to Mary about his time in Washington. You will notice a few names bolded in the correspondence and can find more information about those names at the bottom. Last week we also shared part II of a 3-part series about the history of the Mary Gray Bidwell portrait in the Museum’s collection. We have used it to illustrate many of our recent Bidwell Lore emails. You can read part II of that series HERE.

In a letter from Washington, November 28th, 1805, Barnabas describes to Mary his journey to and arrival in Washington:

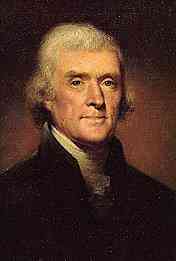

“I tarried in Philadelphia a week, that is until Monday morning last, when I left it, in company with General Varnum, Dr. Fenner, a member of the Senate and Dr. Knight, a member of the House from R. Island, Mr. Bishop of Massachusetts, and Mr. Blake of New York. General Varnum and I got out of the stage at Stalle’s Hotel. General Varnum and I have taken lodgings where he and Col Larned [1] lodged last session, but we had to give one dollar a week more that was given last year. This morning General Varnum and I took a hack to go round and pay our respects to the President (Jefferson) and heads of departments. We waited on the President, and were very politely received. He was dressed plainly, in a blue coat, red or rather reddish vest, olive colored cord or velvet small clothes and white stockings. His person agrees very well with the idea I had formed of him by description, pretty large boned, tall, light hair and complexion, rather freckled. His conversation is easy and sensible. This evening we received cards of invitation to dine with the President on Saturday, which we must decline, on account of a previous engagement. Genl. Varnum and Mr. Macon are both talked of for Speaker. The Tunisian Ambassador is not yet arrived but is on board one of our Frigates, coming up the Potomac. A house is taken for his accommodation. He is said to be a rigid Muslim in his religion, and has 17 attendants. Our foreign relations I find are in some respects unpleasant with regard to Spain, but more so with regard to Gt. Britain.”

Mary responds to his news in an undated letter with her news from Stockbridge and mentions:

“William Jones was married last evening to Clarissa Brown. Dr. James has this day removed his Lucy to Pittsfield. Captain Pepoon occupied his new house. We drank tea with our worthy neighbors Capt. And Mrs. Witon in company with our friend Mrs. Abby Dwight. Mama was of the party tho too deathly ill to enjoy society as I could wish. Dr. Sergeant is to apply the syringe tomorrow. (Bleed her.) Mr. T. Edwards has returned in fine health.“

The reader may remember from previous editions of Bidwell Lore that Timothy Edwards sold Bidwell his house, The Elms.

A letter from Thomas Jefferson to Barnabas Bidwell, Washington, July 5, 1806:

SIR,– Your favor of June the 21st has been duly received. We have not as yet heard from General Skinner on the subject of his office. Three persons are proposed on the most respectable recommendations, and under circumstances of such equality as renders it difficult to decide between them. But it shall be done impartially. I sincerely congratulate you on the triumph of republicanism in Massachusetts. The Hydra of federalism [1] has now lost all its heads but two. Connecticut I think will soon follow Massachusetts. Delaware will probably remain what it ever has been, a mere county of England, conquered indeed, and held under by force, but always disposed to counter-revolution. I speak of its majority only.

Our information from London continues to give us hopes of an accommodation there on both the points of `accustomed commerce and impressment.’ In this there must probably be some mutual concession, because we cannot expect to obtain everything and yield nothing. But I hope it will be such an one as may be accepted. The arrival of the Hornet in France is so recently known, that it will yet be some time before we learn our prospects there. Notwithstanding the efforts made here, and made professedly to assassinate that negotiation in embryo, if the good sense of Bonaparte should prevail over his temper, the present state of things in Europe may induce him to require of Spain that she should do us justice at least. That he should require her to sell us East Florida, [2] we have no right to insist: yet there are not wanting considerations which may induce him to wish a permanent foundation for peace laid between us. In this treaty, whatever it shall be, our old enemies the federalists, and their new friends, will find enough to carp at. This is a thing of course, and I should suspect error where they found no fault. The buzzard feeds on carrion only. Their rallying point is `war with France and Spain, and alliance with Great Britain:’ and everything is wrong with them which checks their new ardor to be fighting for the liberties of mankind; on the sea always excepted. There one nation is to monopolize all the liberties of the others.

I read, with extreme regret, the expressions of an inclination on your part to retire from Congress. I will not say that this time, more than all others, calls for the service of every man; but I will say, there never was a time when the services of those who possess talents, integrity, firmness and sound judgment, were more wanted in Congress. Some one of that description is particularly wanted to take the lead in the House of Representatives, to consider the business of the nation as his own business, to take it up as if he were singly charged with it, and carry it through. I do not mean that any gentleman, relinquishing his own judgment, should implicitly support all the measures of the administration; but that, where he does not disapprove of them, he should not suffer them to go off in sleep, but bring them to the attention of the House, and give them a fair chance. Where he disapproves, he will of course leave them to be brought forward by those who concur in the sentiment. Shall I explain my idea by an example? The classification of the militia was communicated to General Varnum and yourself merely as a proposition, which, if you approved, it was trusted you would support. I knew, indeed, that General Varnum was opposed to any thing which might break up the present organization of the militia: but when so modified as to avoid this, I thought he might, perhaps, be reconciled to it. As soon as I found it did not coincide with your sentiments, I could not wish you to support it; but using the same freedom of opinion, I procured it to be brought forward elsewhere. It failed there also, and for a time perhaps, may not prevail: but a militia can never be used for distant service on any other plan; and Bonaparte will conquer the world, if they do not learn his secret of composing armies of young men only, whose enthusiasm and health enable them to surmount all obstacles. When a gentleman, through zeal for the public service, undertakes to do the public business, we know that we shall hear the cant of backstairs counsellors. But we never heard this while the declaimer was himself a backstairs man, as he calls it, but in the confidence and views of the administration, as may more properly and respectfully be said. But if the members are to know nothing but what is important enough to be put into a public message, and indifferent enough to be made known to all the world; if the executive is to keep all other information to himself, and the House to plunge on in the dark, it becomes a government of chance and not of design. The imputation was one of those artifices used to despoil an adversary of his most effectual arms; and men of mind will place themselves above a gabble of this order. The last session of Congress was indeed an uneasy one for a time: but as soon as the members penetrated into the views of those who were taking a new course, they rallied in as solid a phalanx as I have ever seen act together. Indeed I have never seen a House of better dispositions. They want only a man of business & in whom they can confide to conduct things in the house; and they are as much disposed to support him as can be wished. It is only speaking a truth to say that all eyes look to you. It was not perhaps expected from a new member, at his first session, & before the forms & style of doing business were familiar. But it would be a subject of deep regret were you to refuse yourself to the conspicuous part in the business of the house which all assign you. Perhaps I am not entitled to speak with so much frankness; but it proceeds from no motive which has not a right to your forgiveness. Opportunities of candid explanation are so seldom afforded me, that I must not lose them when they occur.

The information I receive from your quarter agrees with that from the south; that the late schism has made not the smallest impression on the public, and that the seceders are obliged to give to it other grounds than those which we know to be the true ones. All we have to wish is, that at the ensuing session, every one may take the part openly which he secretly befriends. I recollect nothing new and true, worthy communicating to you. As for what is not true, you will always find abundance in the newspapers. Among other things, are those perpetual alarms as to the Indians, for no one of which has there ever been the slightest ground. They are the suggestions of hostile traders, always wishing to embroil us with the Indians, to perpetuate their own extortionate commerce.

I salute you with esteem and respect,

Thomson Joseph Skinner (May 24, 1752 – January 20, 1809), mentioned by Jefferson in the first paragraph of his letter, was an American politician from Williamstown, Massachusetts. In addition to serving as a militia officer during the American Revolution, he served as a county judge and sheriff, member of both houses of the Massachusetts legislature, U.S. Marshal, and member of the United States House of Representatives. He served for two years as Treasurer and Receiver-General of Massachusetts, and after his death, an audit showed his accounts to be deficient for more than the value of his estate, which led to those who had posted bonds on his behalf having to pay the debt.

In the summer of 1776, he carried messages between units in Berkshire County and General Horatio Gates, commander of the Continental Army’s Northern Department in upstate New York. He also served as adjutant of Berkshire County’s 2nd Regiment, adjutant of the Berkshire County 3rd Regiment (Simonds’), and a company commander in the Berkshire County regiment commanded by Asa Barnes. Skinner remained in the militia after the war and rose to the rank of major general. During the Revolution, he served as a member of the court-martial which acquitted Paul Revere’s conduct during the unsuccessful Penobscot Expedition.

He served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1781, 1785, 1789, and 1800. He was a member of the Massachusetts State Senate from 1786 to 1788, 1790 to 1797, and 1801 to 1803. From 1788 to 1807 he was a Judge of the Court of Common Pleas for Berkshire County, and he was chief judge from 1795 to 1807. In 1788 he was a delegate to the state convention that ratified the United States Constitution, and voted in favor of ratification.

From 1791 to 1792 he served as Berkshire County Sheriff. In 1792 Skinner, recognized as a Federalist, was a presidential elector, and supported the reelection of George Washington and John Adams. Skinner was a founding trustee of Williams College, served on the board of trustees from 1793 to 1809, and was treasurer from 1793 to 1798.

Skinner represented Massachusetts’s 1st congressional district (Berkshire County) in the U.S. House for part of one term and all of another, January 1797 to March 1799. He was again elected to the U.S. House in 1802, this time from the renumbered 12th District, and served from March 1803 until resigning in August 1804. Skinner, by now identified with the Jeffersonian or Democratic-Republican Party, lost to John Quincy Adams, the Federalist candidate, in an 1803 election for U.S. Senator. From 1804 to 1807 Skinner served as U.S. Marshal for Massachusetts. From 1806 to 1807 he was Treasurer and Receiver-General of Massachusetts.

After Skinner’s death, an 1809 audit revealed that his accounts as state treasurer were in arrears for $60,000, while his estate was valued at only $20,000. Several of the individuals who had posted surety bonds to guarantee his performance as treasurer paid portions of the remaining $40,000 obligation in order to satisfy Skinner’s debt.

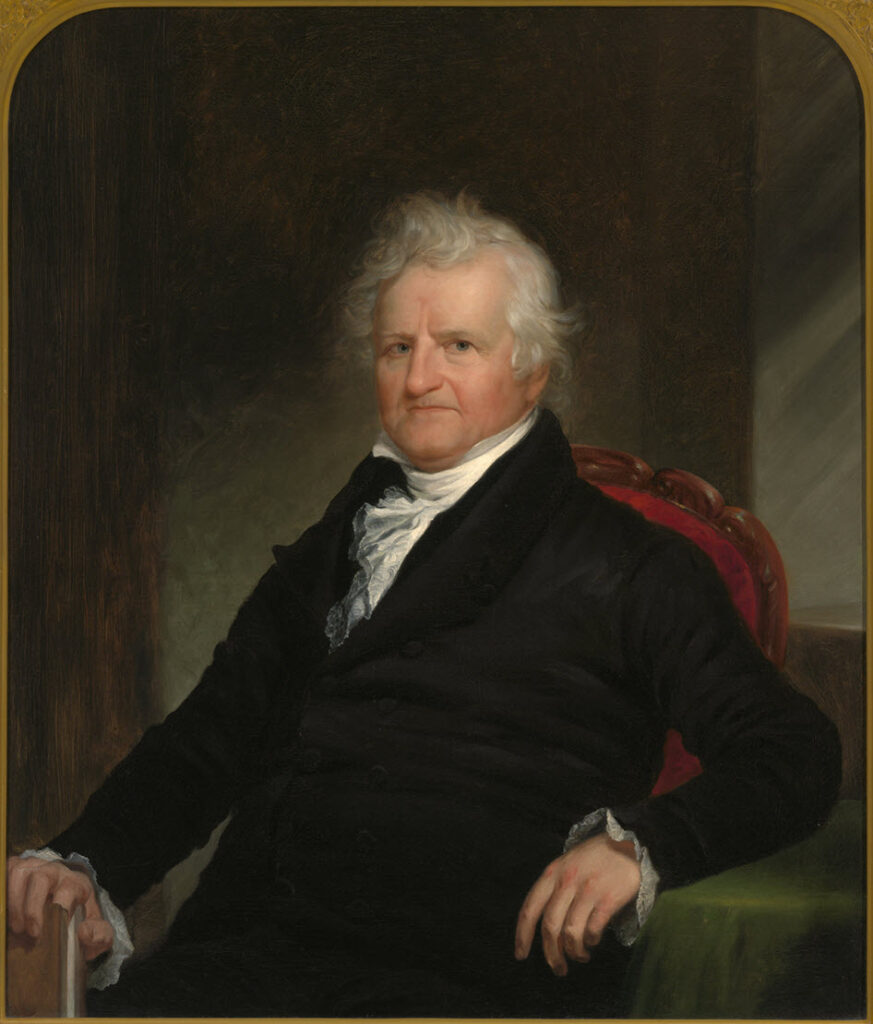

Joseph Bradley Varnum (January 29, 1751 – September 21, 1821), mentioned by both Bidwell and Jefferson, was a U.S. politician of the Democratic-Republican Party from Massachusetts. He served as a U.S. Representative and United States Senator, and held leadership positions in both bodies.

A native of Dracut, Massachusetts, Varnum was the son of farmer, militia officer, and local official Samuel Varnum and Mary Prime. He received a limited formal education, but became a self-taught scholar. Varnum became a farmer, and at age 18 received his commission as a captain in the Massachusetts militia. He commanded Dracut’s militia company during the American Revolution and remained in the militia afterward, eventually attaining the rank of major general in 1805.

Varnum took part in the government of Massachusetts following independence, including as a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1780 to 1785 and member of the Massachusetts State Senate from 1786 to 1795. Despite not being an attorney, Varnum also served as a judge, including terms as a Justice of the Massachusetts Court of Common Pleas and Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Court of General Sessions. He was a member of the U.S. House from 1795 to 1811, and was Speaker of the House from 1807 to 1811. Varnum served in the U.S. Senate from 1811 to 1817, and was the Senate’s President pro tempore from 1813 to 1814.

After leaving the U.S. Senate, Varnum served in the Massachusetts State Senate until his death. He died in Dracut on September 21, 1821, and was buried at Varnum Cemetery in Dracut

Finally, the Hornet, mentioned by Jefferson in the 2nd paragraph of his letter, was launched 28 July 1805, in Baltimore, Master Commander Isaac Chauncey in command.

The Hornet’s design was a compromise between the six original U.S. frigates and coastal gunboats championed by President Thomas Jefferson. The fledgling Navy needed a light-draft vessel that was fast and maneuverable, but also possessing sufficient firepower to deter or defeat enemy ships. Hornet’s design is attributed to Josiah Fox but her builder, William Price, is said to have altered it based on the successful lines of the Baltimore Clipper, of which he had significant experience.

During his time as captain, Chauncey reported significant problems with Hornet’s rigging, hindering her overall potential. In response to these reports, Hornet‘s sister ship, Wasp, constructed at the Washington Navy Yard had her rigging changed to three masts and afterward reported excellent performance at sea.

[1] Congressman Simon Larned from Pittsfield, 1804-1805, held the Berkshire Congressional seat prior to Bidwell.

[2] Samuel Harrison Smith, Gazette newspaper.

[3] Jacob Crowninshield was a congressman.

[4] The Federalist Party was losing its grip on New England. Jefferson’s Republican Party was gaining strength and would dominate politics through additional presidents. This was the beginning of the two-party system.

[5] Barnabas helped to pass legislation that provided money for the purchase of Florida.